In my last post, I discussed some ways to avoid nested code in Python and discussing the “filter” and “map” functions I mentioned the lambda functions.

After that article, some reader asked me to write a little more about this topic, so … here I am. :)

Let’s start with a mantra. If you want to know what something is, in Python, just use your REPL.

So, start the Python REPL and define a lambda:

Python 3.6.2 |Anaconda custom (64-bit)| (default, Sep 19 2017, 08:03:39) [MSC v.1900 64 bit (AMD64)] on win32

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> my_lambda = lambda x: x+1

Now, try to ask Python what is “my_lambda”

>>> print(my_lambda)

<function <lambda> at 0x0000021D14663E18>

It turns out that a “lambda” is… just a function!

Basically, a lambda is just an anonymous function that can be used “inline” whenever your code expects to find a function. In Python, in fact, functions are first-class objects and that basically means that they can be used like any other objects. They can be passed to other functions, they can be assigned to a name, they can be returned from a function and so on.

So, in our first example, we just defined a function that takes an argument (x), sums the value 1 to the input argument, and returns the result of this operation.

What’s the name of the function? It has no name actually, and so I had to assign this anonymous function to the name “my_lambda” to be able to use it in my code.

Now I can hear some of you saying:

Why bother with this stuff? Why not just use a standard named function? Couldn’t I write something like this?

>>> def my_sum_function(x):

... return x+1

...

>>> print (my_sum_function)

<function my_sum_function at 0x0000021D14D83E18>

Yes, you could actually… and I will tell you something more: you can pass this function as well to other functions.

In our example, if we use:

>>> print(list(map(my_lambda, range(10)))) [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

we get the same results of writing:

>>> print(list(map(my_sum_function, range(10))))

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

So, why bother with lambda functions?

Well… it’s just a matter of style and readability, because as we will keep saying: readability counts (“The Zen Of Python”, rule #7).

The case of the RPN Calculator

Let’s pretend that one of your customers asked you to create a program to simulate a “Reverse Polish Notation calculator” that they will install on all their employees’ computers. You accept this work and get the specs for the program:

The program should be able to do all the basic operations (divide, sum, subtract, multiply), to find the square root of a number and to power to 2 a number. Obviously, you should be able to clear all the stack of the calculator or just to drop the last inserted number.

RPN Calculator for newbies If you already know what is a RPN calculator, skip this part. If you do not know what is the Reverse Polish Notation, but you are curious, just check this out. If you do not know anything about the Reverse Polish Notation and you want just a brief explanation to keep reading this article… go ahead. The Reverse Polish Notation was very relevant in 70’s and 80’s as Hewlett-Packard used it in their scientific calculators and I personally love this notation. Basically in a RPN calculator you have a “stack” where you put the operands with a LIFO (last in, first out) logic. Then, when you press the button to compute an operation, the calculator takes out from the stack all the operands that the operation ask for, compute the operation and put the result back to the stack. So, let’s do an example. You want the result of the operation 5 x 6. In a standard calc you would act this way:

- press 5

- press *

- press 6

- press = and on the display you get the result : 30. In a RPN calculator, you act this way:

- press 5

- press ENTER (and the number 5 is put on the stack)

- press 6

- press ENTER (and the number 6 is put on the stack)

- press * Now, before pressing the ‘’ symbol your stack was like this: - 5 6 - after pressing the ‘’ symbol, you find on the stack just the result: 30. That’s because the calculator knows that for a multiplication you need two operands, so it has “popped” the first value (6 — remember, it’s a stack, it’s LIFO), then it has “popped” the second value (5), it has executed the operation and put back the result (30) on the stack. RPN calculators are great since they do not need expressions to be parethesized and there’s more: they’re cool! :)

Now, you accepted the job and you have to start working, but since the deadline of the project is very tight, you decide to ask Max, your IT artist, of writing a GUI for the calculator and Peter, your new intern, of creating the “engine” of this calculator software.

Let’s focus on Peter’s work.

Peter’s work

After a while, Peter comes proudly to you asserting he has finished coding the calculator engine.

And that’s what he has done so far:

"""

Engine class of the RPN Calculator

"""

import math

class rpn_engine:

def __init__(self):

""" Constructor """

self.stack = []

def push(self, number):

""" push a value to the internal stack """

self.stack.append(number)

def pop(self):

""" pop a value from the stack """

try:

return self.stack.pop()

except IndexError:

pass # do not notify any error if the stack is empty...

def sum_two_numbers(self):

op2 = self.stack.pop()

op1 = self.stack.pop()

self.push(op1 + op2)

def subtract_two_numbers(self):

op2 = self.stack.pop()

op1 = self.stack.pop()

self.push(op1 - op2)

def multiply_two_numbers(self):

op2 = self.stack.pop()

op1 = self.stack.pop()

self.push(op1 * op2)

def divide_two_numbers(self):

op2 = self.stack.pop()

op1 = self.stack.pop()

self.push(op1 / op2)

def pow2_a_number(self):

op1 = self.stack.pop()

self.push(op1 * op1)

def sqrt_a_number(self):

op1 = self.stack.pop()

self.push(math.sqrt(op1))

def compute(self, operation):

""" compute an operation """

if operation == '+':

self.sum_two_numbers()

if operation == '-':

self.subtract_two_numbers()

if operation == '*':

self.multiply_two_numbers()

if operation == '/':

self.divide_two_numbers()

if operation == '^2':

self.pow2_a_number()

if operation == 'SQRT':

self.sqrt_a_number()

if operation == 'C':

self.stack.pop()

if operation == 'AC':

self.stack.clear()

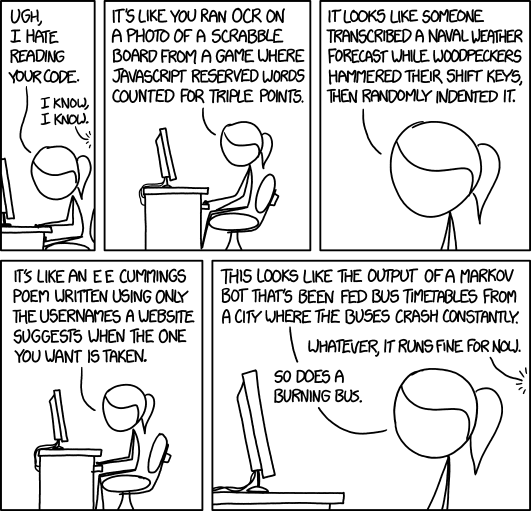

In a moment he understands that you’re looking at him shocked and states: “my code runs fine”.

Now, let’s clarify one thing: Peter’s right. His code runs (so does a burning bus…). Nevertheless, his code sucks. That’s it.

So let’s have a look at how we can improve this “stuff”.

The first problem here is the code duplication. There’s a principle of software engineering that is called “DRY”. It stands for “Don’t Repeat Yourself”.

Peter has duplicated a lot of code because for every single function he has to get the operands, compute the operation and put the result back to the stack. Wouldn’t it be great if we could have a function that does exactly this job, computing the operation we request? How can we achieve this?

Well, it’s really simple actually, because as we said earlier… functions are first-class objects in Python! So, Peter’s code can be simplified a lot.

Let’s have a look at the functions we have to provide.

All the standard operations (divide, sum, add and multiply) needs two operands to be computed. The “sqrt” and the “pow2” functions need just one operand to be computed. The “C” (to drop the last item in the stack) and “AC” (to clear the stack) functions, don’t need any operand to be computed.

So, let’s rewrite Peter’s code this way:

"""

Engine class of the RPN Calculator

"""

import math

class rpn_engine:

def __init__(self):

""" Constructor """

self.stack = []

def push(self, number):

""" push a value to the internal stack """

self.stack.append(number)

def pop(self):

""" pop a value from the stack """

try:

return self.stack.pop()

except IndexError:

pass # do not notify any error if the stack is empty...

def sum_two_numbers(self, op1, op2):

return op1 + op2

def subtract_two_numbers(self, op1, op2):

return op1 - op2

def multiply_two_numbers(self, op1, op2):

return op1 * op2

def divide_two_numbers(self, op1, op2):

return op1 / op2

def pow2_a_number(self, op1):

return op1 * op1

def sqrt_a_number(self, op1):

return math.sqrt(op1)

def compute(self, operation):

""" compute an operation """

if operation == '+':

self.compute_operation_with_two_operands(self.sum_two_numbers)

if operation == '-':

self.compute_operation_with_two_operands(self.subtract_two_numbers)

if operation == '*':

self.compute_operation_with_two_operands(self.multiply_two_numbers)

if operation == '/':

self.compute_operation_with_two_operands(self.divide_two_numbers)

if operation == '^2':

self.compute_operation_with_one_operand(self.pow2_a_number)

if operation == 'SQRT':

self.compute_operation_with_one_operand(self.sqrt_a_number)

if operation == 'C':

self.stack.pop()

if operation == 'AC':

self.stack.clear()

def compute_operation_with_two_operands(self, operation):

""" exec operations with two operands """

try:

if len(self.stack) < 2:

raise BaseException("Not enough operands on the stack")

op2 = self.stack.pop()

op1 = self.stack.pop()

result = operation(op1, op2)

self.push(result)

except BaseException as error:

print(error)

def compute_operation_with_one_operand(self, operation):

""" exec operations with one operand """

try:

op1 = self.stack.pop()

result = operation(op1)

self.push(result)

except BaseException as error:

print(error)

Isn’t it better? The duplicated code is far less than before and looks at the functions, all they do is to compute the operation and return the results. They are no longer in charge of getting operands and pushing the result to the stack, the readability of the code is definitely improved!

Now, looking at the code, the first thing I really hate is all the “ifs” in the compute function. Perhaps replacing them with a “switch” function… if only the switch function would exist in Python! :)

But we can do something better. Why don’t we create a catalog of the available functions and then we just use this catalog to decide which function to use?

Why don’t we use a dictionary for that?

Let’s try to modify our code again:

"""

Engine class of the RPN Calculator

"""

import math

class rpn_engine:

def __init__(self):

""" Constructor """

self.stack = []

self.catalog = self.get_functions_catalog()

def get_functions_catalog(self):

return {"+": self.sum_two_numbers,

"-": self.subtract_two_numbers,

"*": self.multiply_two_numbers,

"/": self.divide_two_numbers,

"^2": self.pow2_a_number,

"SQRT": self.sqrt_a_number,

"C": self.stack.pop,

"AC": self.stack.clear}

def push(self, number):

""" push a value to the internal stack """

self.stack.append(number)

def pop(self):

""" pop a value from the stack """

try:

return self.stack.pop()

except IndexError:

pass # do not notify any error if the stack is empty...

def sum_two_numbers(self, op1, op2):

return op1 + op2

def subtract_two_numbers(self, op1, op2):

return op1 - op2

def multiply_two_numbers(self, op1, op2):

return op1 * op2

def divide_two_numbers(self, op1, op2):

return op1 / op2

def pow2_a_number(self, op1):

return op1 * op1

def sqrt_a_number(self, op1):

return math.sqrt(op1)

def compute(self, operation):

""" compute an operation """

if operation in ['+', '-', '*', '/']:

self.compute_operation_with_two_operands(self.catalog[operation])

if operation in ['^2', 'SQRT']:

self.compute_operation_with_one_operand(self.catalog[operation])

if operation in ['C', 'AC']:

self.compute_operation_with_no_operands(self.catalog[operation])

def compute_operation_with_two_operands(self, operation):

""" exec operations with two operands """

try:

if len(self.stack) < 2:

raise BaseException("Not enough operands on the stack")

op2 = self.stack.pop()

op1 = self.stack.pop()

result = operation(op1, op2)

self.push(result)

except BaseException as error:

print(error)

def compute_operation_with_one_operand(self, operation):

""" exec operations with one operand """

try:

op1 = self.stack.pop()

result = operation(op1)

self.push(result)

except BaseException as error:

print(error)

def compute_operation_with_no_operands(self, operation):

""" exec operations with no operands """

try:

operation()

except BaseException as error:

print(error)

Wow, almost all our “if(s)” are gone! And now we have a catalog of functions that we can expand as we want. So for example, if we need to implement a factorial function, we will just add the function to the catalog and implement a custom method in the code. That’s really good!

Even if …

It would be great to act only on the catalog, wouldn’t it? But wait… shouldn’t we talk about lambdas in this article?

Here’s where lambdas can be useful! We don’t need a standard defined function for a simple calc, we need just an inline lambda for that!

"""

Engine class of the RPN Calculator

"""

import math

class rpn_engine:

def __init__(self):

""" Constructor """

self.stack = []

self.catalog = self.get_functions_catalog()

def get_functions_catalog(self):

return {"+": lambda x, y: x + y,

"-": lambda x, y: x - y,

"*": lambda x, y: x * y,

"/": lambda x, y: x / y,

"^2": lambda x: x * x,

"SQRT": lambda x: math.sqrt(x),

"C": self.stack.pop,

"AC": self.stack.clear}

def push(self, number):

""" push a value to the internal stack """

self.stack.append(number)

def pop(self):

""" pop a value from the stack """

try:

return self.stack.pop()

except IndexError:

pass # do not notify any error if the stack is empty...

def compute(self, operation):

""" compute an operation """

if operation in ['+', '-', '*', '/']:

self.compute_operation_with_two_operands(self.catalog[operation])

if operation in ['^2', 'SQRT']:

self.compute_operation_with_one_operand(self.catalog[operation])

if operation in ['C', 'AC']:

self.compute_operation_with_no_operands(self.catalog[operation])

def compute_operation_with_two_operands(self, operation):

""" exec operations with two operands """

try:

if len(self.stack) < 2:

raise BaseException("Not enough operands on the stack")

op2 = self.stack.pop()

op1 = self.stack.pop()

result = operation(op1, op2)

self.push(result)

except BaseException as error:

print(error)

def compute_operation_with_one_operand(self, operation):

""" exec operations with one operand """

try:

op1 = self.stack.pop()

result = operation(op1)

self.push(result)

except BaseException as error:

print(error)

def compute_operation_with_no_operands(self, operation):

""" exec operations with no operands """

try:

operation()

except BaseException as error:

print(error)

Wow, this code rocks now! :)

Even if…

Let’s pretend that we have to add the factorial function, could we just modify the catalog?

Unfortunately no.

There’s another place we have to modify… we have to modify also the compute function because we need to specify that the factorial function is a “one operand function”.

That’s bad, we do know that it is a one operand function, it’s obvious since we need to call the math.factorial(x) function passing just the x argument. If only there were a way to determine how many arguments a function needs at runtime…

There is actually. In the “inspect” module, there’s a “signature” function that can help us inspect the signature of our method at runtime. So, let’s start the REPL and do a quick test:

>>> a = lambda x, y: x + y

>>> from inspect import signature

>>> my_signature = signature(a)

>>> print(my_signature)

(x, y)

>>> print (my_signature.parameters)

OrderedDict([(‘x', <Parameter "x">), (‘y', <Parameter "y">)])

>>> print (len(my_signature.parameters))

2

Yes, amazing. We could determine at runtime how many operands our function needs!

"""

Engine class of the RPN Calculator

"""

import math

from inspect import signature

class rpn_engine:

def __init__(self):

""" Constructor """

self.stack = []

self.catalog = self.get_functions_catalog()

def get_functions_catalog(self):

""" Returns the catalog of all the functions supported by the calculator """

return {"+": lambda x, y: x + y,

"-": lambda x, y: x - y,

"*": lambda x, y: x * y,

"/": lambda x, y: x / y,

"^2": lambda x: x * x,

"SQRT": lambda x: math.sqrt(x),

"C": lambda: self.stack.pop(),

"AC": lambda: self.stack.clear()}

def push(self, number):

""" push a value to the internal stack """

self.stack.append(number)

def pop(self):

""" pop a value from the stack """

try:

return self.stack.pop()

except IndexError:

pass # do not notify any error if the stack is empty...

def compute(self, operation):

""" compute an operation """

function_requested = self.catalog[operation]

number_of_operands = 0

function_signature = signature(function_requested)

number_of_operands = len(function_signature.parameters)

if number_of_operands == 2:

self.compute_operation_with_two_operands(self.catalog[operation])

if number_of_operands == 1:

self.compute_operation_with_one_operand(self.catalog[operation])

if number_of_operands == 0:

self.compute_operation_with_no_operands(self.catalog[operation])

def compute_operation_with_two_operands(self, operation):

""" exec operations with two operands """

try:

if len(self.stack) < 2:

raise BaseException("Not enough operands on the stack")

op2 = self.stack.pop()

op1 = self.stack.pop()

result = operation(op1, op2)

self.push(result)

except BaseException as error:

print(error)

def compute_operation_with_one_operand(self, operation):

""" exec operations with one operand """

try:

op1 = self.stack.pop()

result = operation(op1)

self.push(result)

except BaseException as error:

print(error)

def compute_operation_with_no_operands(self, operation):

""" exec operations with no operands """

try:

operation()

except BaseException as error:

print(error)

As someone said, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” :)

Note that in this last code we have modified the zero operands functions in the catalog from

"C": self.stack.pop,

"AC": self.stack.clear

to

"C": lambda: self.stack.pop(),

"AC": lambda: self.stack.clear()}

Why?

Well, the problem is that in the *compute *function we are trying to determine the number of parameters from the signature of the method. The problem is that for built-in methods written in C, we can’t do that.

Let’s try it by yourself, start a REPL:

>>> from inpect import signature

>>> a = []

>>> my_sig = signature(a.clear)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "C:UsersMASTROMATTEOAppDataLocalContinuumanaconda3libinspect.py", line 3033, in signature

return Signature.from_callable(obj, follow_wrapped=follow_wrapped)

File "C:UsersMASTROMATTEOAppDataLocalContinuumanaconda3libinspect.py", line 2783, in from_callable

follow_wrapper_chains=follow_wrapped)

File "C:UsersMASTROMATTEOAppDataLocalContinuumanaconda3libinspect.py", line 2262, in _signature_from_callable

skip_bound_arg=skip_bound_arg)

File "C:UsersMASTROMATTEOAppDataLocalContinuumanaconda3libinspect.py", line 2087, in _signature_from_builtin

raise ValueError("no signature found for builtin {!r}".format(func))

ValueError: no signature found for builtin <built-in method clear of list object at 0x000001ED6EB18F88>

as you can see we can’t get the signature of a built-in method.

Our possibilities to solve this problem were:

- Handle this special case in our code, trapping the exception raised when we tried to get the signature for the self.stack.pop() function and the self.stack.clear() function

- Encapsulate the built-in functions in void lambdas, so as to have the signature functions extract the signature from our void lambda function and not from the built-in function contained.

And we have obviously chosen the second possibility since it is the most “Pythonic” we had. :)

That’s all folks. Today’s article has explored some aspect of functions and lambdas in Python and I hope you got the message I wanted to send.

think twice, code once.

Sometimes developers are lazy and don’t think too much at what can mean maintain bad code.

Let’s have a look at the first Peter’s code of the article and try to figure out what could have meant to add the factorial function then. We should have created another function, duplicated more code, and modified the “compute” function, right? With our last code we just need to add a single line to our catalog:

"!": lambda x: math.factorial(x),

Try to think at what could have meant to add another feature to the program for logging all the calculations requested and the given results. We had been supposed to modify a dozen functions of our code to add the feature right? And we would have had to modify as well all the new functions that we will have inserted from now on. Now we can add the feature just in the three methods that really compute the requested calculation depending on the number of the operands requested.

Wait, three methods? Wouldn’t it be possible to have just a method that works regardless of the number of operands that are requested by the function? :)

Happy coding!

D.